Microservices Communication Patterns: Sync vs Async

A deep dive into communication patterns for microservices. Learn when to use synchronous vs asynchronous communication and how to implement them effectively.

The industry has largely moved past the “microservices for the sake of microservices” hype. We have entered the era of Pragmatic Service Architecture. We no longer ask if we should split a monolith; we ask how to manage the cognitive and operational load of the distributed system we have already built.

The most common point of failure in these systems is not the code within the services, but the space between them. In real production systems, the choice between synchronous and asynchronous communication is rarely about “better” or “worse”—it is about which set of failure modes you are willing to manage.

The Synchronous Fallacy: REST, gRPC, and the Illusion of Simplicity

Synchronous communication is the “natural” way to build. Service A calls Service B and waits for a response. It mirrors how we write local functions, making it easy for developers to reason about.

However, teams often discover the hard way that synchronous calls are the primary vector for cascading failures.

The Problem with Temporal Coupling

In a synchronous world, Service A is only as healthy as Service B. If Service B experiences a latency spike, Service A’s threads begin to saturate.

In 2026, with the high concurrency requirements of agentic AI workflows, this temporal coupling is a silent killer.

One of the most frequent production disasters occurs when a deep call chain (A → B → C → D) hits a bottleneck at the end. The resulting backpressure is not handled; instead, it consumes resources up the chain until the entire cluster becomes unresponsive.

REST vs gRPC in 2026

While REST over HTTP/1.1 remains the legacy glue of the web, internal production traffic has shifted almost entirely to gRPC and the Connect protocol.

- gRPC / Protobuf

Binary serialization and HTTP/2 multiplexing are now table stakes for reducing egress costs—a major concern in modern cloud budgets.

- The Connect Protocol

Connect has gained traction by providing gRPC-compatible APIs that work seamlessly over HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2, allowing teams to get gRPC performance without the operational friction of raw gRPC infrastructure.

When to Use Synchronous Communication

Synchronous communication still plays a critical role in modern systems:

- Querying State

When a user is waiting for a response (e.g., fetching a profile).

- Immediate Validation

When a workflow cannot proceed without a definitive “Yes/No” from a downstream authority.

- Internal Control Planes

Where low-latency coordination matters more than total decoupling.

The Asynchronous Pivot: Events, Streams, and the Cost of Consistency

Asynchronous communication—typically via a message broker such as Kafka, Pulsar, or NATS—is the standard for any operation that changes state.

By 2026, the industry has matured in its understanding of Event-Driven Architecture (EDA). Events are no longer treated as side effects; they are treated as the source of truth.

The Shift from Kafka to NATS JetStream

While Apache Kafka remains dominant for high-throughput data pipelines and analytics ingestion, many platform teams have shifted toward NATS for microservice communication.

- Kafka scales extremely well but introduces significant operational complexity (partitions, rebalancing, consumer groups).

- NATS JetStream provides a lighter, service-native messaging layer that supports pub/sub and built-in request–reply, greatly simplifying the developer experience.

The Reality of Eventual Consistency

Asynchronous systems trade availability for consistency.

This works well—until a customer asks why their balance hasn’t updated yet.

Teams often learn this lesson too late: implementing Saga patterns or CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) is mandatory for non-trivial async systems.

Without compensating transactions, databases slowly fill with partial and inconsistent states.

The “Third Path”: Request–Reply over Async

A pattern that has solidified by 2026 is synchronous-style communication over asynchronous infrastructure.

Using brokers like NATS or RabbitMQ for request–reply enables:

- Location Transparency

Services communicate via subjects, not IPs or DNS.

- Load Leveling

Brokers absorb bursts instead of overwhelming downstream services.

- Observability

Requests and responses are visible at the messaging layer without sidecars.

Production Realities: Scale, Cost, and Failure

In practice, the “best” communication pattern is often dictated by constraints you can’t ignore: latency budgets, cross-region egress costs, incident blast radius, and how retries behave under load. The sections below cover the recurring failure modes teams run into once systems scale beyond a handful of services.

Latency and eBPF

The traditional service-mesh sidecar tax has been mitigated by eBPF-based networking. Modern platforms now implement mTLS, retries, and circuit breaking at the kernel level.

While this reduces latency, it does not eliminate architectural coupling.

The Egress Trap

In multi-region deployments, microservice chatter is expensive.

- Async systems allow batching and compression, reducing egress costs by 40–60%.

- Sync calls—especially large JSON payloads—are often the largest hidden line item in cloud bills.

Failure Modes: Retries and Idempotency

Idempotency is not optional.

- In synchronous systems, a timeout does not mean failure—it means no response. Retrying without idempotency can double-charge customers.

- In async systems, at-least-once delivery guarantees duplicates will happen eventually.

Systems must be designed accordingly.

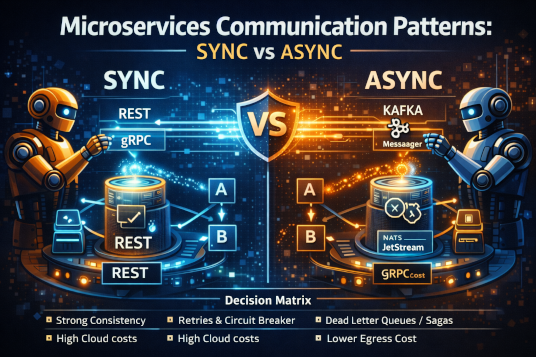

Decision Matrix

| Constraint | Prefer Synchronous (gRPC / Connect) | Prefer Asynchronous (NATS / Kafka) |

|---|---|---|

| User Waiting | Yes | No |

| Data Consistency | Strong / Immediate | Eventual |

| System Coupling | Tight (Temporal) | Loose (Spatial) |

| Failure Handling | Retries / Circuit Breakers | DLQs / Sagas |

| Conceptual Complexity | Low | High |

| Operational Cost | High (Egress, Scaling) | Lower (Batching) |

Conclusion

The choice between synchronous and asynchronous communication is one of the most consequential decisions a software architect makes.

Synchronous communication is a bet on simplicity and speed—provided you can manage the fragility of tight coupling. Asynchronous communication is a bet on resilience and scale—provided you can manage distributed state and delayed consistency.

In 2026, the most successful systems are hybrid:

- gRPC / Connect for read-heavy, latency-sensitive operations

- Event-driven messaging for every state change and cross-domain interaction

Engineering is the art of choosing constraints.

Don’t choose async because it is “modern.”

Don’t choose sync because it feels “easy.”

Choose the failure modes you are best prepared to debug at 2:00 AM.

Engineering Team

The engineering team at Originsoft Consultancy brings together decades of combined experience in software architecture, AI/ML, and cloud-native development. We are passionate about sharing knowledge and helping developers build better software.